By Karen Davis, PhD, President of United Poultry Concerns

On March 14, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof published

To Kill a Chicken

in which he discusses the new undercover video by Mercy For Animals documenting the torture of chickens by workers at a chicken slaughterhouse in North

Carolina. The agony of the chickens in the video is the agony that millions of chickens suffer every day, everywhere on earth. Here is what awaits them:

Since chickens are unseen by most people as a result of their being thought of as food, advertised as food, obliterated into food, and raised and

slaughtered out of sight in most places, we depend on investigators like MFA to take us into the underworld from which chickens emerge as

“food.” And we look to journalists like Nicholas Kristof to help get the message out to the public through outlets like The New York Times.

But every time Kristof writes about chickens, glad as I am for the coverage, a wave of sadness and anger adds to the feelings evoked by the misery and

cruelty revealed in the video.

Here, I will skip over Kristof’s inaccurate claim that the pre-slaughter electrified waterbath through which chickens are dragged face down in the

slaughterhouse “is meant to knock them unconscious” and that an alternative procedure known as controlled atmosphere stunning or killing puts

the birds “painlessly to sleep.” (For information see poultry slaughter process.)

In this writing I want to point, rather, to where Kristof says, in To Kill a Chicken, “I raised chickens as a farmboy. They’re not as smart as

pigs or as loyal as dogs, but they make great moms, can count and have distinct personalities. They are not widgets.” No, they are not.

The issue I am raising is why does he feel the need to insert into his column a gratuitous slur on the comparative intelligence and “loyalty”

of chickens?

In Is an Egg for Breakfast Worth This? in The New York Times,

April 11, 2012, Kristof discusses an HSUS investigation at Kreider Farms, an

industrial family farm operation in Pennsylvania. There, in the midst of the horror being recounted about the Kreider Farms’ battery-caged hens, he

pauses to tell us that “Like many readers, I don’t particularly empathize with chickens. It’s their misfortune that they lack big eyes.

As a farmboy from Yamhill, Ore., I found our pigs to be razor smart, while our geese mated for life and our sheep and cattle had distinct personalities.

The chickens were the least individualistic of the animals we raised. (I’ll get letters from indignant chicken lovers, I know!)”

What if, instead of chickens, Kristof was discussing the plight of poultry slaughterhouse workers from diverse backgrounds and he interrupted the narrative

to proclaim, “Like most readers, I don’t particularly empathize with Latinos. It’s their misfortune that they lack blue eyes. I’ll

get letters from indignant Latino lovers, I know!)”

To cite one more example, in “A Farm Boy Reflects” in The New York Times, July 31, 2008,

Kristof speculates that in a century or two our descendants “will look back on our factory farms with uncomprehending revulsion. But in the meantime, I love a good burger.”

I would like to know how, by this logic, he believes the transition will occur. Because each burger-loving Kristof has to be multiplied by billions.

As usual, Kristof talks in this column about growing up on the family farm, raising and slaughtering animals, terrorizing geese and doing terrible things

even to the “intelligent” animals, and boasting that he eats them anyway, only “I draw the line about animals being raised in cruel

conditions.”

If we wonder where factory farming comes from – the mentality and brutality of it – we need look no further than where Kristof says: “Our

cattle, sheep, chickens and goats certainly had individual personalities, but not such interesting ones that it bothered me that they might end up in a

stew. Pigs were more troubling because of their unforgettable characters and obvious intelligence. To this day, when tucking into a pork chop, I always

feel as if it is my intellectual equal.”

Kristof isn’t the only journalist somewhat on “our side” who writes this way about farmed animals. He’s one of those writers who

say that they oppose “factory farming” while bragging that they eat animals regardless, who poke fun at chickens while tossing them a crumb of

condescending “respect,” who reassure the public that even the animals they “admire” are still perfectly suited for slaughter for

culinary pleasure, notwithstanding the size or brilliance of their eyes or the complexity of their intelligence, feelings, family life or personalities,

and even though they know that raising and slaughtering animals, whether on a factory farm or a family farm, is neither necessary nor truly humane.

|

In To Kill a Chicken, Kristof cites a poll in which he says that “81 percent of consumers said that it was important to them that chickens they eat

be humanely raised.” Such polls with these types of responses are questionable. Before he died in 1998, animal rights activist and chicken rights

champion Henry Spira (see my Loving Tribute to Henry Spira) used

to cite them hopefully as signs of progress, but are they? The responses are passive. It’s easy to say, “I want the chickens I eat to be

humanely raised.” The next question should be, “But suppose chickens are not, and cannot, be humanely raised in any meaningful sense of the

word – what then?”

I hope we will have polls and an engaged journalism that generate more than just words from people who say that they care how chickens and other farmed

animals are treated. It’s great that they care, but what next? What are caring people going to do with their care? That, for the animals, is

the question, the only one that counts. – Karen Davis

|

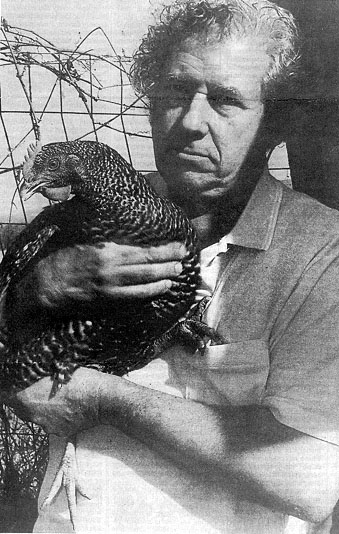

Henry Spira. “Animals are not edibles.”

|